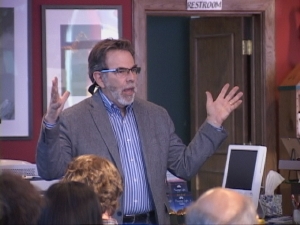

TreePeople founder, Andy Lipkis

If Andy Lipkis succeeds, eventually his work may help the Owens Valley and other places from which Los Angeles sucks water.

Gigi Coyle of Big Pine introduced Lipkis recently when he offered a talk at the Mountain Light Gallery in Bishop about what he does. More than 50 came to hear about TreePeople, the organization Lipkis founded 40 years ago when he was just 15 years old. Since then, the group has planted thousands of trees in LA and helped develop new ways to capture water in the Los Angeles basin.

What started as a modest group of people who wanted to save trees from LA smog has grown into a group supported by many government agencies and big corporations, including the Annenberg Foundation. While many admire the work of TreePeople, some here have noted that it’s a bittersweet fact that as more trees grow in LA, they die in the Owens Valley.

Lipkis told the crowd gathered that TreePeople’s mission is to inspire people to take personal responsibility for the urban environment. Their early and continued focus remains on planting trees and helping neighborhoods to accept personal involvement with the trees. Lipkis said global climate change and the water shortage have prodded the group to go further with the environment.

They now support projects that direct rainwater into the underground acquirers to manage LA as a watershed. They advocate permeable paving, special drains, cisterns and

TreePeople’s efforts may some day help places like the Owens Valley.

what they call forest-mimicking innovations as ways to direct rainwater into the ground. They want to see what they call a “Functioning Community Forest” in every LA neighborhood. Lipkis said the vision of TreePeople is to transform LA into a City that generates 50% of its own water and sustains a 25% tree canopy – in short, a fully functioning watershed.

TreePeople has managed to engage the Department of Water and Power and other City agencies in this work. Lipkis has demonstrated that it costs less to create water saving projects than to deal with flooding and wastewater. He said his group has also transformed neighborhoods from concrete streets that attract drug dealers to urban forests where residents step up to the care of the trees and find a different atmosphere where they live.

Lipkis added that, “Our work brings agencies together to manage LA as a forest and to harvest rainwater.” He said the agencies find it’s not too expensive when they combine their budgets. TreePeople’s work is also targeted to find jobs for chronically unemployed young people.

So, what does it all mean to the Owens Valley? Maybe sometime in the distant future LA will generate its own water. Meanwhile, TreePeople was a message for Owens Valley people that it takes organization and dedication to save the environment.

I’m retarded

Bye everyone…

Love You!!!

DT, The big offender in ground water pollution at SG valley was JPL lab in Pasadena. I have been drinking the polluted water for most of my life. Also, if you call the water conservationist at PWP they will tell you about the projects to recharge local aquifers such as… Read more »

JPL is far from the only source of groundwater pollution in the San Gabriel Valley. Don’t ignore the many defense plants in the Pomona area, especially the big missile plant, now closed and converted to retail, alongside Hwy 71. The San Fernando and San Gabriel Valleys were centers of Cold… Read more »

The one problem with this is that the aquifers in the San Fernando and San Gabriel Valleys are both heavily contaminated with hexavalent chromium and trichloroethane, the legacy of Cold War era weapons and aerospace development programs conducted in those valleys. Examples are the old Lockheed Skunk Works in Burbank… Read more »